Interview with Fabrizio Crisafulli.

BY Ludovico Cantisani.

Fabrizio Crisafulli, born 1948, is an Italian theater director and visual artist, an exponent of the so-called research theater. Trained in the fertile environment of the Roman cellars, following Giuliano Vasilicò for a long time, his conception of theater and art has always placed great emphasis on the creative and expressive potential of light. His Teatro dei luoghi project was reported at the 1998 Ubu Awards. Among the various critical publications devoted to his work are Fabrizio Crisafulli. A Theater of Being (Editoria & Spettacolo, 2010), edited by Silvia Tarquini, and the recent Light and the City. Fabrizio Crisafulli and the RUC students at Roskilde Lysfest (Lettera Ventidue, 2022), edited by Bjørn Laursen, dedicated to the Lysfest (Festival of Light) realized by Crisafulli between 2013 and 2017 in Roskilde, Denmark, at the invitation of the local university, which also awarded him an honorary degree in 2015.

We interviewed Crisafulli about his entire journey and his search for light, from his beginnings in the world of independent theater in the 1970s to his most recent installation Bagliori, created in Principina a Mare in September 2022.

In a lecture-self-portrait you gave at the MACRO in Rome a few years ago1, you recount that you began your directorial research starting with light because, in general, it seemed to be the least cared-for and in-depth element in theatrical practices. From what moment did you begin to be specifically interested in the creative potential of light?

It was probably the frequentation of the so-called “Roman cellars” in the 1970s, a very important phenomenon of Italian theatrical research, that gave me the decisive push in this direction. In the shows I was seeing and in the experiences I was coming into contact with at that time – I am thinking of Carmelo Bene, Memè Perlini and especially Giuliano Vasilicò, whose path I followed closely for years – one could see an employment of light that was very different from what I had seen in theaters up to that time. Light had a poetic presence that often equaled that of the word and the actor. In Vasilicò, in particular, it also contributed substantially to structuring the performance dramaturgically and rhythmically. This seemed to me to finally reconnect light, even in its scenic declination, to the autonomous force and energetic and generative quality it possesses in reality.

Can you outline the most important features of your light research?

In principle, I try precisely to make stage light acquire the strength and determining power proper to light in reality, where it is a primary, originating element that determines the organization and quality of life and actions. I think for this reason that stage light should not be relegated to a secondary position, as is often the case in common practices, where it is generally prepared in the last days of rehearsals. I think that this devaluation of the rising role of light makes the theater lose its ability to resonate the real. The question is not to imitate natural light, but to recover the energy and arousing power of light, whatever form it takes on stage, even the most abstract. There have been in the history of theater several moments of awareness of this aspect. Some of its implications were already quite clear, for example, to certain Baroque theater treatisers, to many Enlightenment intellectuals, to great stage reformers of the years at the turn of the nineteenth century such as Adolphe Appia and Edward Gordon Craig. And they can be found, more or less under the radar, in much theatrical research from the historical avant-gardes to the present. But, in general, practices have continued to prefer the usual path, although there are extraordinary exceptions. This is a topic on which I have had the opportunity to reflect a great deal, trying to draw on my own operational experience in identifying its many aspects.2

When and how did your concrete research in this specific field begin?

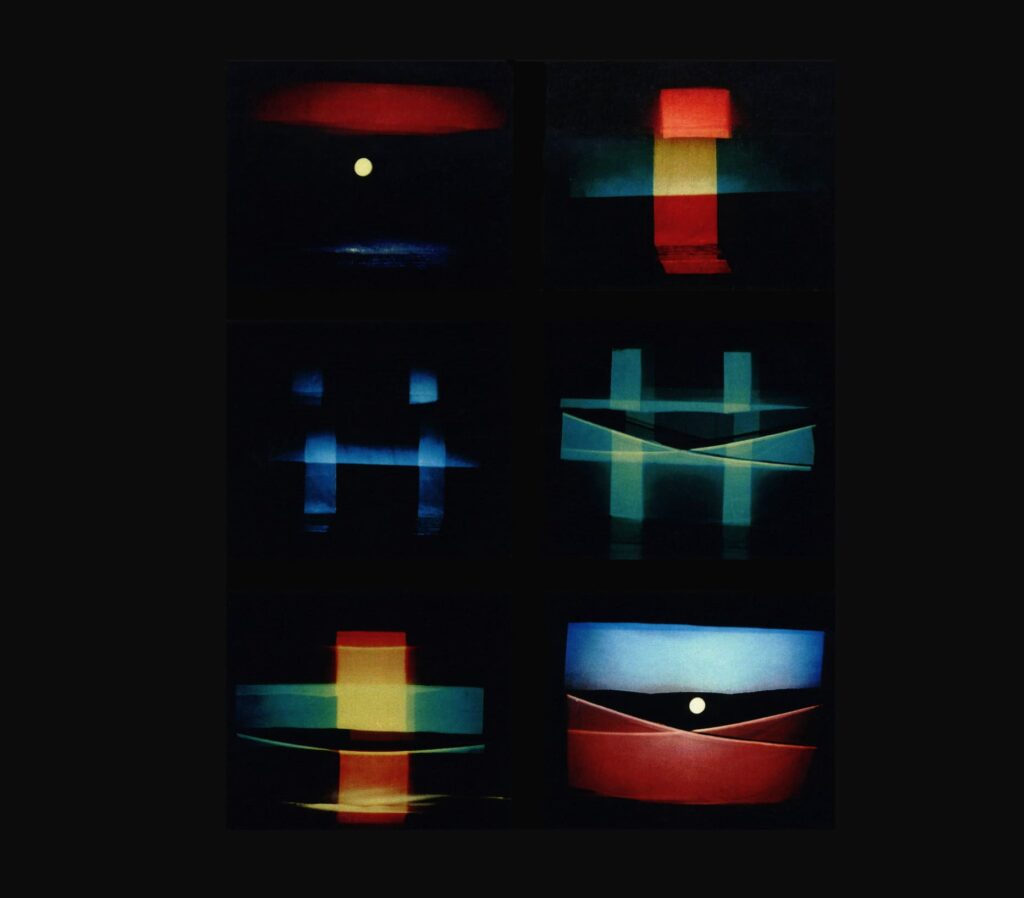

In the second half of the 1980s I started workshops, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Catania, in a small Italian-style theater. I aimed to explore the possible articulations of light as language, with a view to making it regain strength and authority on stage. In that specific field of study, we were making performances without text or actors, based entirely on light, objects, and sound. To test their effectiveness from the point of view we were interested in, we would systematically present them to the audience. The central question was to investigate the capacity that light possesses to independently initiate and carry on its own discourse. And to elaborate a sufficiently articulated language to enable it then to develop relationships on par with other expressive elements, in works with performers and the rest. In the workshops, we were trying to construct sensible concatenations of “happenings” with light: dramaturgies. It was not about supporting the narrative and dramatic development of a theatrical piece, nor, on the other side, about making son et lumière performances, successions of “effects” in relation to music. Instead, it was a matter of making theater and dramaturgy in the proper sense, with light. Leading the latter beyond the sphere to which it is predominantly made to belong, that of the image, to make it act in an important way as time and as action.

Does your research on light also feed on the comparison with other artistic languages?

Of course, inevitably. And the comparison happens both in the specific processes of construction of the individual work and in the general research on language. Regarding the latter, a very strong reference has always been music. Light can be composed like music: it possesses the same malleability and availability to elaboration, the same souplesse-as Appia said, who wrote fundamental pages on this3-the same capacity to produce meaning and poetry, and the same possibilities of linguistic exactitude. I have conducted workshops on light continuously over the years, alongside my directorial work with actors, dancers, literary references. And that has been a very important experience for me. That, in my directorial and dramaturgical work, has put me in a position to propose to the performers and all the collaborators, already at the initial stage of each creation, concrete terrains of relationship, articulated, living, with their own logics: “worlds,” in which, as in reality, light possesses its own laws, and has a great importance and influence on everything that happens.

Another central theme of your research is the concept of “theater of places.” On the occasion of the honorary degree you were awarded in 2015 by the University of Roskilde, Denmark, you gave a lectio magistralis in which you stated that this particular mode of your work “attributes to the place where the performance is constructed and presented a role as a starting element of creation similar to that played by the text in other kinds of theater. ”4 Can you explain in more detail the starting basis and purpose of the theater of places?

It is a kind of work that does not correspond, as perhaps the definition might suggest, with making shows outside theaters. Nor with “setting” work. It does not mean using the venue as a “set,” nor does it mean “adapting” theatrical pieces in non-theatrical spaces. It operates a reversal from the usual way of operating: the place becomes the first point of reference of creation, its matrix. And by place I do not mean only the physical site, but the sphere of relationships that, in the construction of the work, are established with the people, activities, and memories with which it comes into contact, as well as with its material data. Relations that, incidentally, can also occur within the theater, if the theater is considered precisely as a place, with its history, its operating relations, its identity, and not merely a host space and a medium. I say this because, in fact, the moment in which for the first time I had a perception of how the place of relationships can become generative of work, was precisely during the light workshops I mentioned, which were taking place on stage. There was a phase in which, stimulated also by the shortage of resources, we began to turn our attention to the stage and its equipment – wings, backdrops, “Americas,” ropes, counterweights, pulleys, lighting fixtures – seen no longer only as tools and mechanisms, but also as elements bearing history, culture, identity. To see their evocative and potentially poetic side linked, for example, to the memory of stagecraft and the performance represented. There was born a strand of work that we called “dramas of technique,” which brought the stage and its equipment into play as symbolic and poetic generators, which became absolute protagonists, together with the stagehand-poets who moved them, of the performance. I had then, already in those early years, many opportunities to verify how the indications that place provides and the impetus it exerts on choices are even more extensive when working in non-theatrical type sites, urban or “natural” spaces that they may be, which of course are usually even more powerful and implication-laden pre-existences. But, as I have said, this is not to say that place theater is distinguished by the fact that it takes place in non-theatrical spaces.

How come you use the term site-specific theater and not site-specific theater?

Mike Pearson5 has rightly observed how the site-specific adjective applied to performance is very generic, and is therefore understood in different ways depending on the artists and contexts that employ it. Moreover, the term refers to place understood as a physical location (site) and not in a broader sense. I needed to use a definition more relevant to my own work, which I identified at some point, through concrete work and reflections6.

What is the relationship between the theater of places and the use of light?

As I said, in this kind of work, place becomes the “matrix” of creation. This also applies to light, which does not relate to place in terms of “illumination,” but in a more complex way. One could say that it tends to create with the place an exchange. More than an element “projected” from outside, it is matter “belonging” to it. And from the place, in a sense, it seems to “come”. I am not talking about sending light toward the audience, an eventuality that can also happen, but about a kind of mutual determination between light and place. The most immediate case of understanding is perhaps that of light taking on the forms of architecture as a matrix, to some extent “tracing” them, reworking them and returning them in a new “vision.” But the question is more articulated and concerns the relationships with all the elements of the scene: the actors, the objects, the sound. And it brings movement into play.

Are you referring to the use of mapping techniques?

Also. Or rather, I would say that mapping is an issue that should be considered in the context of issues such as those just mentioned. Definitions such as projection-mapping or video-mapping refer today to a precise form of contemporary urban performance. But this is something that has more distant motives and origins. If one thinks of the arrangement of flame lamps along the main lines of architecture in the events of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, one realizes how they were mappings. Mappings made by hand through the physical arrangement of lumens on plinths, cornices and other parts of the architecture. In this way the building became precisely a “matrix” of the forms of light. But what was this kind of choice related to? To understand well what it is about one would have to look at all the ways of mutual determination between object and light over time. To the different forms they have taken. Which is a whole story. I can also think of later examples: pre-cinema, nineteenth-century optical shows, the magic lantern even before electricity. And to episodes closer to us: in the late 1960s, in the Haunted Mansion in Disneyland, California, the faces of a group of singers filmed in 16 mm. were projected onto their respective sculptural portraits, which then, even with the help of sound, seemed to come alive and sing. That, too, was mapping. As was At the Shrink’s, a 1975 installation by Laurie Anderson, an extraordinary artist of great technical inventiveness who has always been an important reference in my workshops, in which an alter ego of the author, recorded in Super8 as she talks to her psychoanalyst, was projected onto a clay figurine of the artist herself sitting in an armchair.7

Within your path, have you used such modes?

These are modes immanent in the work, the use of which is always linked to specific motives. In my workshops of the 1980s, for example, we used techniques of light-object or light-body adhesion, Employing the analog tools then available, such as film projections, fixed (slides) and moving (Super8 film), and especially handmade masks arranged on the top of lecture boards, according to a modality elaborated in the workshops, which I often used later on as well. The modesty well in view, the first show of my company, born in 1991 just from the Sicilian workshops, was moreover based, as far as the light was concerned, on devices of that kind, which allowed to create continuous exchanges and reversals between real and virtual, body and image. We were not using the term mapping, which perhaps did not yet exist. I was very interested in exploring these modes of exchange and, in the case of that show, reasoning about the process of substitution of reality operated in our time by the image. Generally, I tend to frame the use of such techniques within a more general discourse on language. Sometimes, in the reasoning that always accompanies workshops, it has been useful for me to make theoretical distinctions between different categories of light. For didactic purposes as well, at one point I found myself, for example, distinguishing between functional light, which is light that serves to illuminate the scene and the actors, and positive light, as I called it, which is instead light-form and light that moves and acts; thus light not “to see,” but “to be seen.” The identification of this pair supported me in the concrete work on the dynamics and interchanges between light and object, and beyond. The use of mapping should also be seen within a linguistic framework, for it to have a ground on which to progress. Among other things, the introduction to su tempo of digital projections and ad hoc software, in addition to creating new opportunities, seems to me to have contributed to “isolating” this modality and making it think of itself as a “genre.” And this, from my occasional observatory of this kind of work, seems to me to have made its use even more vulnerable to what is an ever lurking danger in the design of light in performance, related precisely to its limited linguistic tradition, which is that of effectsism. With often degenerative outcomes, it seems to me, also linked to borrowing from other fields and languages, such as video games.

Were there other kinds of reflections and theoretical distinctions that helped you in your work with light?

An important distinction was that between “illuminated scene” and “illuminating scene,” which concerns the viewer’s perception of the direction of the light, and which, as can be guessed, also has relations to the binomial functional light-positive light: in the first case – that of the “illuminated scene” – the light “goes” from outside to the scene; in the second – the “illuminating scene” – it “goes,” or seems to go, from the scene to the viewer. The distinction came to my mind while reading a 1915 “manifesto” by Enrico Prampolini8 and other Futurist writings where the idea of the “illuminating scene” is combined with that of a set design that is not subordinate to the actor, independent, dynamic, “actress.” A stage that also acts by “sending” light. Sending it apparently (through reflection, or even, in the case of the practices adopted by the Futurists, through the use of photoluminescent colours for the scenography), or actually, by illuminating the audience, as in a crucial moment of Feu d’Artifice, the pioneering show created by Giacomo Balla in 1917, made only of light and scenic elements; a moment in which, in accordance with a very fast and rhythmic score, suddenly and for a few seconds, the room was illuminated9; or as in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s “circular theatre” project, from the early 1930s, where the lights were conceived to be pointed at the spectators from the stage that surrounded them at 360°, to make them part of the show10. In my work I have frequently activated dialectics and exchanges between the illuminated stage and the illuminating stage, which have generally been rather productive, both in terms of the linguistic articulation of light and of symbolic production.

Can you give an example?

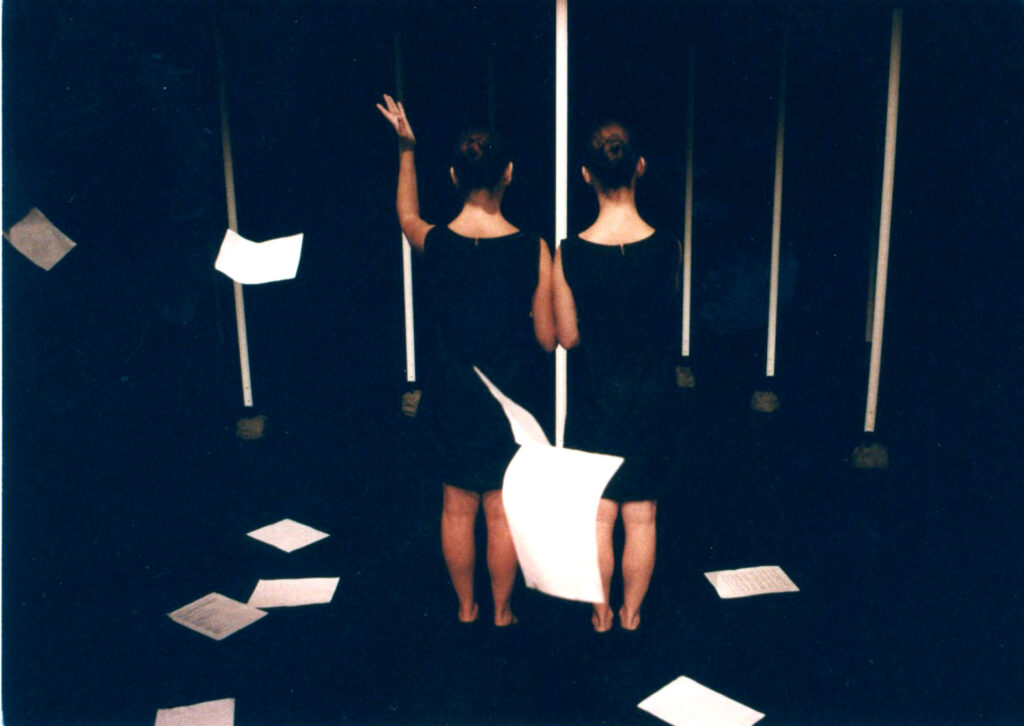

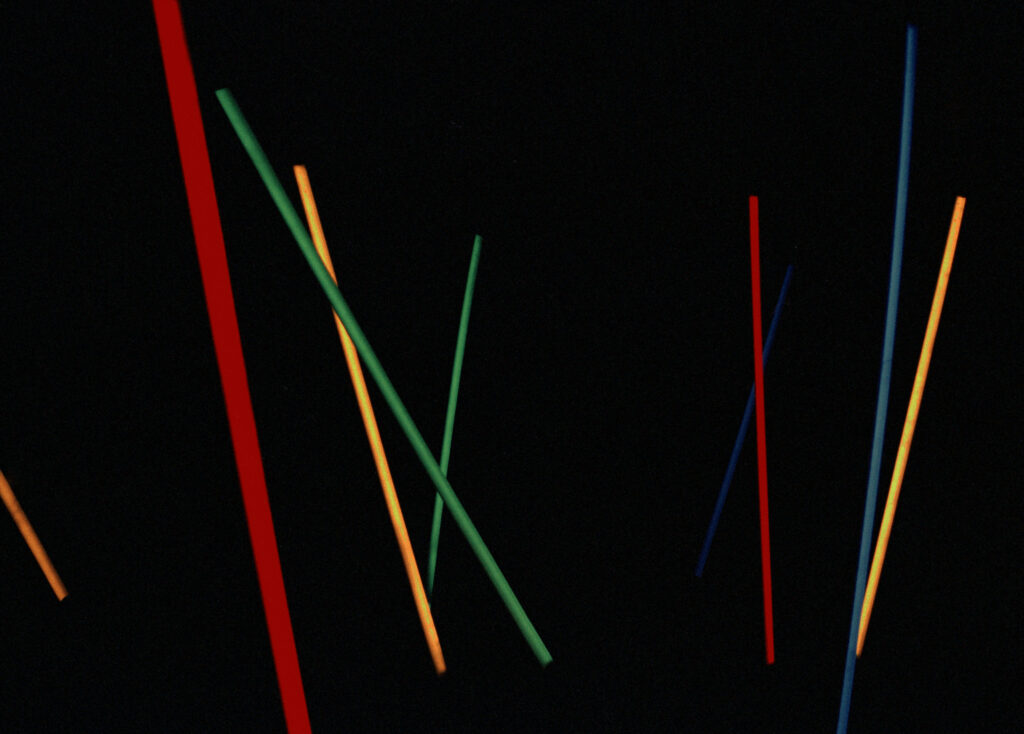

I quote the rods from a 1977 show called Folgore lenta, dedicated to Yves Klein: stage objects that played a significant role in defining the structure and meaning of the work. During the show, the rods were moved by the actresses themselves and placed in different positions at the centre of the stage, entering into different types of relationships with light. They were the “world”. A changing world, which the people on stage simultaneously constructed and found themselves around as a “condition” influencing the actions. At certain moments, the white rods were hit by blades of light (white or coloured, depending on the scene) that perfectly coincided with them. Due to the exact overlapping of light and object, they did not produce shadows, and therefore seemed to light up and emit light like neon lights, like “illuminating” objects, precisely, despite being made of polystyrene. At other moments, however, they received light from wide-beam devices, frontal or backlit. And, producing shadows, brought and their own, they appeared, as they actually were, “illuminated”. At certain moments both types of light were present; therefore the “illuminated” and the “illuminating” coexisted in common situations that were also prolonged, changing, with different degrees of relationship over time. This, in combination with the actions of the actresses, the word, the space, the sound, contributed significantly to articulating the show, on the visual level and on the dramaturgical and meaning level.

Folgore lenta, ideazione di Fabrizio Crisafulli e Andreas Staudinger, regia e luci di Fabrizio Crisafulli, 1997. Nella foto: Irene Coticchio e Barbara de Luzenberger (foto Udo Leitner)

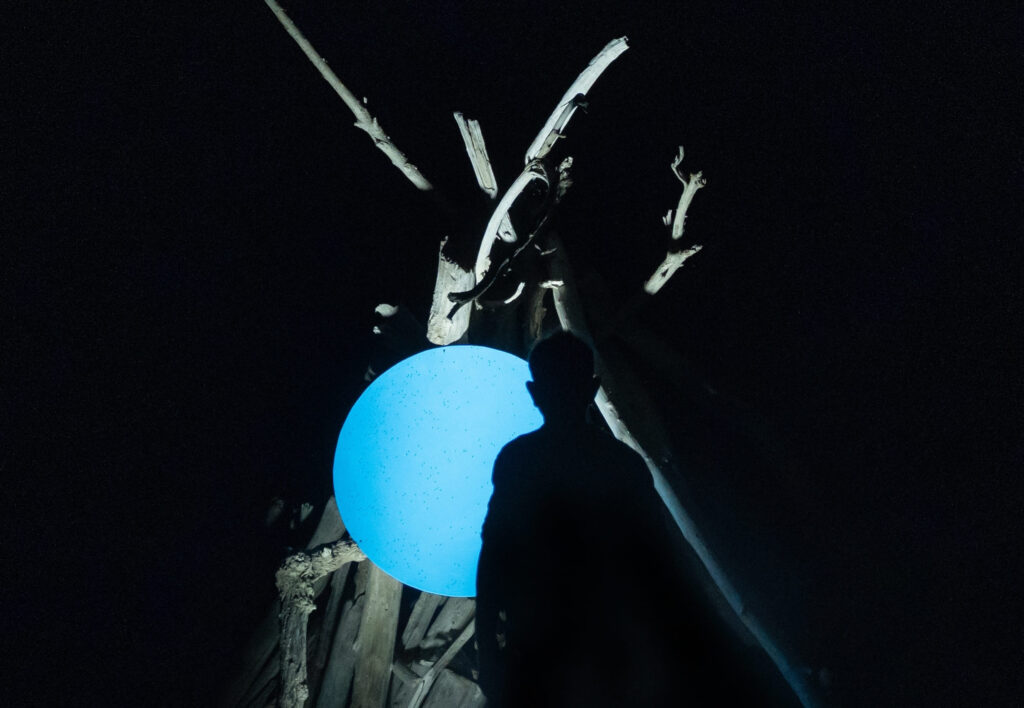

A recent installation of yours, Bagliori, created in Principina a Mare, near Grosseto, in the context of the “Dune” festival, seems to have brought into play light themes like the ones you are talking about. It extended for a few hundred meters along the so-called “beach of the huts”, characterized by constructions spontaneously made with tree trunks, and included luminous presences made of single shapes “applied” to the huts. These, we read in your working notes, “contain within themselves two dimensions – geometry and color – which in their purity are absent from the place. But they were not conceived in opposition to the existing. On the contrary. The act of applying them to the huts corresponds to the operation that for a long time was done by the locals: that of building a fantastic place through successive additions”.

For decades, locals have created these constructions on the beach, as protection from the sun and shelter, which give the place a unique character. Creating a new significant vision starting from such a powerful pre-existence, extending for kilometers, seemed to me at first an almost impossible undertaking. My choices were also directed by this. I gave the intervention a considerable extension, and I arranged the shapes in space so that, despite being distant from each other, they created partial visual continuities. Each shape, in addition to showing itself, signaled in the distance the subsequent shapes, and the existence of a path. The succession in the spectator’s enjoyment of the different “stations” also corresponded to the perception of the site that I had during the inspection, for gradual discoveries of the different huts, and continuous surprises linked to their revelation in succession. As you rightly noted, regarding the light, here too the question of illuminated scene-illuminating scene was brought into play: I used a specific form, based not on movements, successions or temporal dynamics of light, but on the perceptive ambiguity of light and object. To illuminate the shapes, I used fairly generic LED devices, with a non-shapeable beam and non-adjustable aperture; but I pointed them closely, so that they hit the colored shapes first and only marginally the huts, which were perceived in dim light. In this way, the shapes shone in the darkness with an intense light (hence, Bagliori), like “emissions” of shape and color. Even the action that Melissa Lohman, whom I had invited to intervene, created within Bagliori, was part of the path for its sense of belonging to the place. Melissa chose to work in an open structure of logs made up of the remains of a hut destroyed by the storm surges. And, in sensitive contact with the place, she created a direct and subtle performance, which seemed to be “generated” at the same time by the place and the installation. Her costume – red, in two pieces, with a slightly geometric shape – in addition to being an imaginative reference to the idea of the bather, established a connection with the colored silhouettes applied to the huts.

What role did sound have in the installation?

A weaving role, first of all. Andreino Salvadori created in some points of the installation paths made up of noises that seemed to be produced by the site (also for this specific aspect, we gave the place a role of “matrix”): wood, waves, footsteps on the ground. Only in the final part did the sound have a minimally “musical” configuration, as well as a noisy one, in a final area, almost a point of meditation after the long walk, where the spectator found himself in front of a blue circle, a kind of “moon” applied to the last hut of the path.

How did you choose the shapes to apply to the huts?

I chose simple shapes, wooden silhouettes of different sizes, circles, squares, rectangles, triangles, painted with primary colors. The choice was intuitive, partly prompted by the consideration that, in a situation of that kind, those who visit the place at night can hardly avoid remembering it in its daytime aspect; and this led me to also work on the tension between day and night, before and after, lack and presence of pure color, organic shapes of the trunks and exact geometry of the applied shapes. Tension that was combined with that between “illuminated” and “illuminating”, and with the perceptive ambiguity of light and object, which I was talking about. As is usual for me, it was not a work based on direct meanings, but on the activation between the show and the spectator of a circulation of thought, memory, imagination.

You said that you consider your work successful if it teaches you something. What did Bagliori teach you?

One thing he taught me was precisely about shapes. I saw that the attractive power they set in motion in that particular situation was different from shape to shape. More instantaneous and less prolonged was that exerted by triangles and rectangles, more profound and enchanting was that of squares and especially circles, which, with their bright colored surfaces, in some cases stopped the spectator in a prolonged observation, in an almost hypnotic condition. As if by a lunar suggestion or a ganzfeld effect. I remembered the amazement I had felt in perceiving the reaction of the public and my own in front of the large installation The Weather Project by Olafur Eliasson at the Tate Modern in London in 2003. There, as is known, at the center of everything there was a large flat artificial sun, translucent, placed high up in the large Turbine Hall of the museum, which transmitted towards the public the light of a series of monofrequency, yellow lamps behind it. Spectators tended to linger in the space for a long time, in many cases sitting or lying on the floor, attracted by that large, fixed luminous circle; with the contribution, in that case, of the mirrored ceiling that overlooked the entire room and of the artificial fog.

Bagliori, installazione di Fabrizio Crisafulli, “spiaggia delle capanne” di Principina a Mare (GR), 2022 (foto Luca Deravignone).

La performance di Melissa Lohman per Bagliori di Fabrizio Crisafulli, “spiaggia delle capanne” di Principina a Mare (GR), 2022 (foto Luca Deravignone).

What were the reactions of the spectators, local and “foreign”, to Bagliori?

Some have perceived a connection between the work and the commitment to the environment, which is notable locally, given that the “beach of the huts” is located in the Uccellina park and that the context was the “Dune. Arts, Landscapes, Utopias” festival. And this made me very happy. Sometimes this type of connection is felt for accessory choices, such as the use of “green” energy for the lights. In our case, it seems to me that the respect for the place was appreciated, more generally. A respect that is not conservative, but of perspective. I liked the enthusiasm of the people emotionally linked to this magnificent place. And also some singular observations from the “foreigners”: one person, for example, said that “we must have worked very hard to build those log structures to support the colored shapes”, which, in addition to amusing me a lot for the surreal reversal, seemed to me to translate a feeling of unity intervention-place, not hindered by the visionary character of the installation. And this also made me very happy.

In addition to your work in the field of light, you have written extensively on the subject. I was struck by the fact that in both the prefaces to the English and French editions of your volume Luce attiva, the emphasis is placed on the timeliness of the book, despite the fact that the two translations were published several years after its first release in Italian, which was in 2007. Dorita Hannah speaks, in fact, of a “timely” book12 and Anne Surgers of a book “that begins to fill an almost total gap in the French bibliography on the subject of theatrical light”13. Does it seem to you that there is, in general, little attention to the subject of light?

Maybe so. But to find attention, you also have to look at non-specialist fields of activity and thought. And to the past, where you can find very advanced ideas. The famous passage by Giacomo Leopardi comes to mind about the infinite forms and qualities that natural light takes on in its relationships with materials and spaces, in the countless interposed ways through which we perceive it14: a passage that I often point out to my students to help them understand how, in the design phase, deeply observing the relationships that light establishes with things, people, spaces, surfaces, materials, inclinations, the production of shadows, reflections, and the results on apparently insignificant, secondary or distant parts of the scene, is crucial. And how the observation and then the design care of these relationships is just as important as the study and care to be given to direct light and lighting fixtures, to which kids tend to pay more attention, also induced by design with software, carried out on a screen and only at the end verified in real space, in relation to the body, the matter, the depths. I believe that in every era the thought and experience of light have had very high moments. James Turrell has often said how important it was for him and for his great Roden Crater project under construction in Arizona, how much the natives of the area taught him about natural light15. They pointed out to him, for example, how, in that desert, on a moonless night, it is possible to see the shadows produced by the light of Venus; a condition that creates spaces for perception that are not easily imaginable for us contemporaries. But certainly the era in which we live and the technologies at our disposal enable us to notice many other things, as the extraordinary work of Turrell itself demonstrates.

1 Fabrizio Crisafulli, Self-portrait, in AA. VV., Macro Asilo Diario, MACRO/Palaexpo, Rome, 2019.

2Cfr. Fabrizio Crisafulli, Luce attiva. Questioni della luce nel teatro contemporaneo, Titivillus, Corazzano (PI), 2007.

3Cfr. Adolphe Appia, Oeuvres complètes, ed. in 4 tomi elaborata e commentata da M.-L. Bablet-Hahn, L’Age d’Homme, Losanna, 1986.

4Fabrizio Crisafulli, Il luogo, la luce, il corpo del teatro, in «Teatri delle Diversità», n. 73-76, dicembre 2016-maggio 2017, p. I; ediz. originale inglese:Place, Light, Body in Theatre, «Theatre Arts Journal», vol. 4, n. 1, 2017. Al teatro dei luoghi Crisafulli ha dedicato il volume Il teatro dei luoghi: lo spettacolo generato dalla realtà, Artdigiland, Dublino, 2015 e numerose altre pubblicazioni.

5Cfr. M. Pearson, Site-Specific Performance, Palgrave MacMillan, Basingstock (UK), 2010.

6 Cfr. nota 4.

7Cfr. Laurie Anderson, Stories from the Nerve Bible, Harper Perennial, New York, 1994.

8Enrico Prampolini, Scenografia e coreografia futuriste (1915), in Paolo Fossati, La realtà attrezza, Einaudi, Torino, 1977, p. 231.

9Lo spettacolo fu definito dall’artista un “balletto senza ballerini”. Cfr. E. Gigli, Giochi di luce e forme strane di Giacomo Balla, De Luca, Roma, 2005.

10Cfr. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Il teatro totale e la sua architettura, in «Futurismo», n. 13, anno II, 15 gennaio 1933.

11 Cfr. Susan May (a cura di), Olafur Eliasson: The Weather Project, Tate Gallery, Londra, 2003.

12Dorita Hannah, The Event of Light. Foreword, in Fabrizio Crisafulli, Active Light. Issues of Light in Contemporary Theatre, Artdigiland, Dublino, 2013, p. 11.

13Anne Surgers, Eclat de la lumière. Préface, in Fabrizio Crisafulli, Lumière active. Poétiques de la lumière dans le théâtre contemporain, Artdigiland, Dublino, 2015, p. 12.

14Giacomo Leopardi, Zibaldone dei pensieri, frammenti 1744-1745 del 20 settembre 1821.

15Cfr. Gaia Sambonet (a cura di), James Turrell. Dipinto con la luce, Motta Architettura, Milano, 1998.